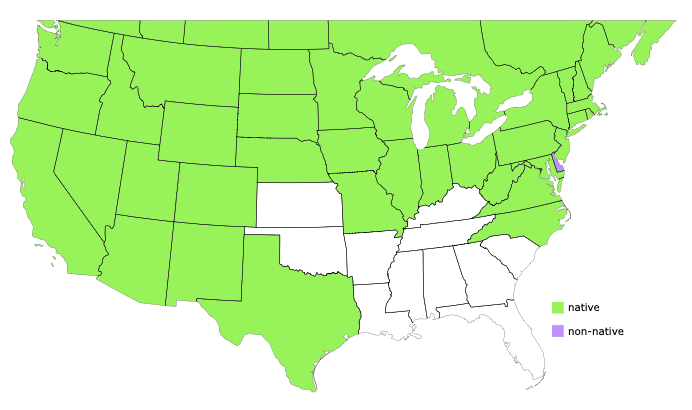

The Quaking Aspen (Populus tremuloides) — known by many names including Trembling aspen, American aspen, white poplar and trembling poplar — is the most widely distributed tree species in North America, in cool regions spanning all of Canada, all of the western US and as far south as West Virginia and Virginia).

The species mainly propagates itself through root sprouts, creating extensive clone colonies that share a single root structure, like Pando in Utah, considered the heaviest and oldest living organism on the planet.

While clones in the West grow slow and old, like Pando and others in the Rocky Mountain and Great Basin regions of at least 8,000 years old, individual trees in the humid East are faster growing and shorter lived (50-60 years in the Great Lakes, up to 150 in the West.) Stands may also consist of a single clone or a mosaic of different clones, with a wide variation in genetic traits existing between clones, the USDA says.

The species is also an “aggressive pioneer species,” according to the U.S. Forest Service, readily colonizing burned areas and persisting even when subject to frequent fires, with seedling establishment more regular on sites exposed by wildfires despite drought conditions.

Identification

Quaking Aspen grows tall trunks up to 80 feet tall, with smooth pale bark that does not peel and is marked by black “eye-like” scars. Bark is relatively smooth, greenish-gray when young, becoming identifiably white with furrowed/darkened by thick black horizontal scars and prominent black knots in age. Leaves are simple and alternate, 1.5-3 inches long and nearly round with finely serrated leaf margins. Younger trees and root sprouts also have much larger (4-8in), nearly triangular leaves.

The common name identifiers of Quaking and Trembling are a result of the leaves flexible, flattened petioles, which allow them to flutter and dance in the wind. These glossy leaves, though dull on their back, become golden-to-yellow in autumn.

Aspen stands are good firebreaks, often dropping crown fires in conifer stands because of small flammable accumulation, and allow more ground water recharge than conifer forests and protect against soil erosion, according to the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service.

The tree exhibits fast growth, resilience in extreme weather and is home to many animal species, making it a key pioneer for reforestation, climate adaptation and biodiversity. Because of these attributes, the Quaking Aspen’s almost identical-twin, the Common or European Aspen (Populus tremula), was named 2026 Tree of the Year by the Dr. Silvius Wodarz Foundation, an annual award given since 1989 to help promote tree species identification and appreciation.

“Quaking aspen … is a quintessential “foundation species” in early-successional forest ecosystems throughout much of North America,” according to a 2013 Forest Ecology and Management research article that studied defensive adaptations of the species. “Although subject to damage by hundreds of species of herbivores, aspen has persisted in these environments due largely to a suite of defense strategies.”

These defensive strategy include:

- Resistance (traits that deter herbivores): producing tannins that deter browsing.

- Tolerance (traits that facilitate recovery from damage): high intrinsic growth rates, significant storage capacity and physiological plasticity.

- Escape (traits that reduce exposure to herbivores): clones exhibit substantial variation in timing of spring bud break to potentially protect high-value tissue.

Uses

Quaking aspen is an important fiber source, particularly for pulp, flake-board and other composite products, providing light wood with little shrinkage that makes it useful for pallets, boxes, veneer and plywood. The wood characteristics make it useful in ”miscellaneous” products, like animal bedding, tongue depressors, beehives, spoons, matchsticks and ice cream sticks.

“It makes good playground structures because the surface does not splinter, although the wood warps and susceptible to decay,” USDA says in a fact sheet.

The large-scale use of Aspen to feed livestock and wildlife, due to its high nutritional value, has also led to the failure of aspen to regenerate in many areas. This is being compounded by warming climate that is expected to expand the range of insect defoliators that target aspen (bad bugs that eat all their leaves), researchers say.

In nature, the buds and bark supply food for snowshoe hares, moose, black bears, cottontail rabbits, porcupines, deer, grouse and mountain beavers, which store their logs for winter food. All members of the Populus genus serve as food for caterpillars for various moths and butterflies.

Leave a comment