The Northern Red Oak (Quercus rubra) is a large, deciduous tree native to the Northeastern and North-Central U.S. that grows to about 75 feet tall. The long-lived tree has a rounded outline, with upright spreading branches from a large single trunk.

The tree likes full sun, well drained, acidic soil. Sandy loams are best. Northern Red Oak withstands urban conditions well, but needs ample room to develop and grows rapidly for an oak.

Acorns are large and brown with a flat, saucer-like cap. Buds are chestnut brown. Bark is brown to black on old branches and trunks, featuring shallow fissures and ridges that deepen as the tree gets older. Smooth bark on young branches.

Mature Summer foliage color is dark green. Leaves are 5-8 inches long and 4-6 inches wide, consisting of 7 to 11 bristle-tipped broad leaves.

Autumn foliage is a mixture of russet-red, yellow and tan, with color developing late and capable of being “quite good or disappointing.”

Last year, the state of Connecticut saw a significant increase in acorn abundance in the red oak group compared with past years, a phenomenon referred to as either a “mast year” or “bumper crop,” according to the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, or CAES.

Except in the northern corners of the state, a record number of red oak acorns hit the ground in Fall 2024, with nearly 87% of all red oaks studied by CAES documented with acorns, compared with a historical average of 57%. This contrasts acorn crop failure that occurred in the white oak group, with only 9% of trees producing acorns, compared with a historical average of 25%.

A famous specimen, the Ashford Oak, grew to boast a trunk 26 feet in circumference, located on Giant Oak Lane off Route 44 (about a mile west of intersection with Route 44A. The tree was awarded first prize as the largest tree entered in the 1927 tree contest, holding the title until 1972, and was passed by George Washington when it was only 100. The Ashford Oak has unfortunately has since died, after losing its long-standing battle with injuries sustained in a 1938 hurricane.

One of the most commercially important tree species of New England forests, the species is under heightened surveillance by arborists due to the significant harmful impact of Red Oak Wilt in the Midwest and the disease’s appearance in Upstate New York.

Oak Wilt

Oak Wilt is an invasive vascular disease of oak trees, particularly red oaks, caused by the fungal pathogen Bretziela fagacearum. The pathogen is spread above ground via nitidulid beetles, or below ground via root transmission (cooties).

The disease mainly effects the red oak group, which in addition to the Northern Red Oak includes the Black Oak, Pin Oak and Scarlet Oak, according to Robert Cole, forester for the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation.

White oaks generally do not form the spore mats that transmit the disease and seal off limbs exposed to infected beetles, so they are not a concern for infection, Cole said, speaking at the Branching Out Together conference (agenda).

Suspected Oak Wilt seen in Connecticut should be reported immediately. Photos of suspect trees with these symptoms should be submitted to Nate Westrick (nathaniel.westrick@ct.gov) at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station (123 Huntington St., New Haven) for further investigation.

Symptoms of Oak Wilt include: tree wilt, flagging and most significantly premature summer leaf drop.

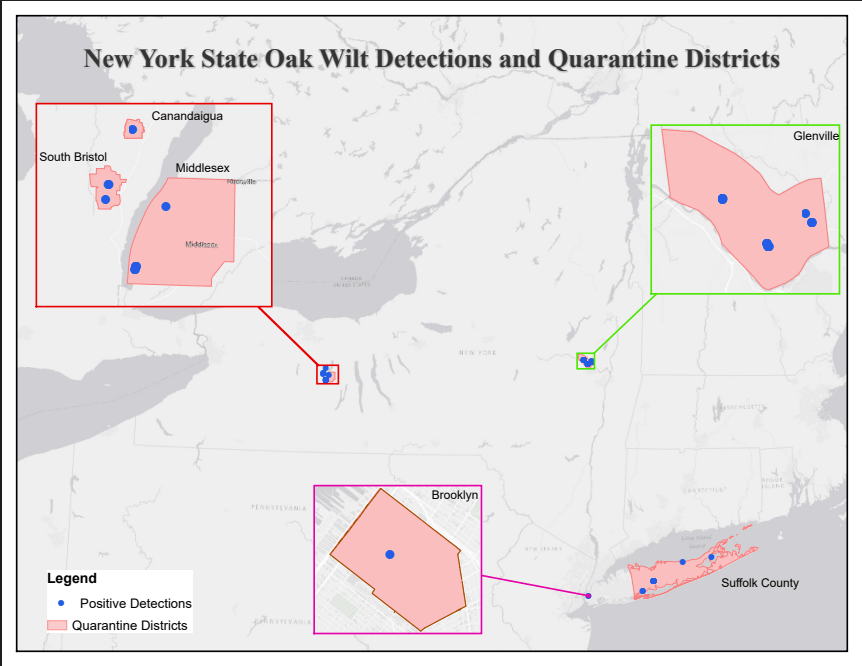

Oak wilt has been detected in several Midwestern states (significantly impacting Michigan and parts of Minnesota), Texas, Pennsylvania and New York, where it was first detected in 2008 near Schenectady. It has since been detected at locations in the Finger Lakes region, Long Island and Brooklyn.

The Connecticut Department of Energy and Environment has yet to detect oak wilt in the state, but the threat of the disease to a valuable state resource and its proximity in New York means that the state and residents should be aware of the symptoms and how to detect and report a potentially infected specimen, Cole said.

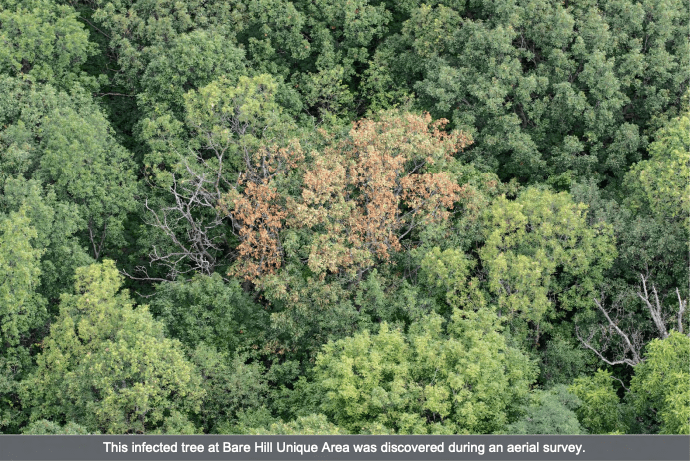

“We really want people to focus on the leaves in mid-Summer,” Cole said, explaining how landowners can determine if their trees may be infected. “The other trees are full and green, looking healthy, while the Oak [infected by Oak Wilt] stand out quite a bit. You can have fully discolored leaves. You can have leaves falling that have very little or no discoloration on them.”

Regardless of the discoloration, the most clear and obvious symptom to look for in Summer is [red] Oak trees that have dropped at least 80% of their leaves, according to Cole. “You can see these trees are still hanging on to a few, but there’s not much there, and the rest eventually will drop,” he said.

Despite the potential danger of Oak Wilt, Connecticut has yet to be affected and has the benefit of a well-developed monitoring system in New York State, giving hope that most red oaks in will be protected against the disease as many other species face high mortality rates due to invasive pathogens and predators (Dutch Elm Disease, Hemlock Woolly Adelgid, etc).

Leave a comment