Eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) is a coniferous, shallow-rooted tree native to eastern North America, widespread through much of the Great Lakes, Appalachian Mountains, Northeastern U.S. and Maritime Canada. The trees are long-lived, with many examples living for more than 500 years!, and can grow to heights of over 100 feet.

Hemlocks are tolerant of shade, moist soil and slopes, and feature characteristic drooping branches, making them popular as ornamental trees. The trees require moist, cool conditions and grow well with 30 to 50 inches of precipitation, growing in pure or mixed stands at sea level. In Connecticut, most trees are concentrated in the northwest corner, with large stands also occurring in the northeast and southeast.

Eastern hemlocks’ bark was an important source of tannin for the leather tanning industry, with its wood being used in construction and for railroad ties. Due to its widespread distribution, long lifespan and shade tolerance, hemlock plays a distinctive role in forest ecosystems, filling a niche in riparian areas that allows the regulation of microclimates, according to the U.S. Forest Service.

The Yale-Myers forest, which encompasses 7,840 acres in the towns of Ashford, Eastford, Union and Woodstock, Connecticut, hosts “a large component of hemlock,” alongside mixed hardwood and pine, Yale School of the Environment says.

Additionally, dense stands of the species provide habitat to wildlife, with research finding that the hemlocks may support more than 1,000 species, USF says. When deciduous trees have not yet leafed out in the spring, hemlocks provide shade, keeping streams cool and slowing snowmelt throughout the watershed, according to Grace Haynes, researcher at Cornell University’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

Though not considered a valuable timber species, hemlocks play a vital ecological role in forests and wetlands, Carole Cheah said in a 2019 research paper, published in The Habitat.

Unfortunately, the tree has long been threatened in its native range by the spread of the invasive Hemlock Woolly Adelgid (HWA), which infests and eventually kills trees, leading the species to being listed as Near Threatened status. HWA has wrought destruction on Connecticut’s hemlock trees — alongside fellow non-native pest EHS (elongate hemlock scale) and the native hemlock borer — exacerbating tree decline resulting from escalating drought conditions.

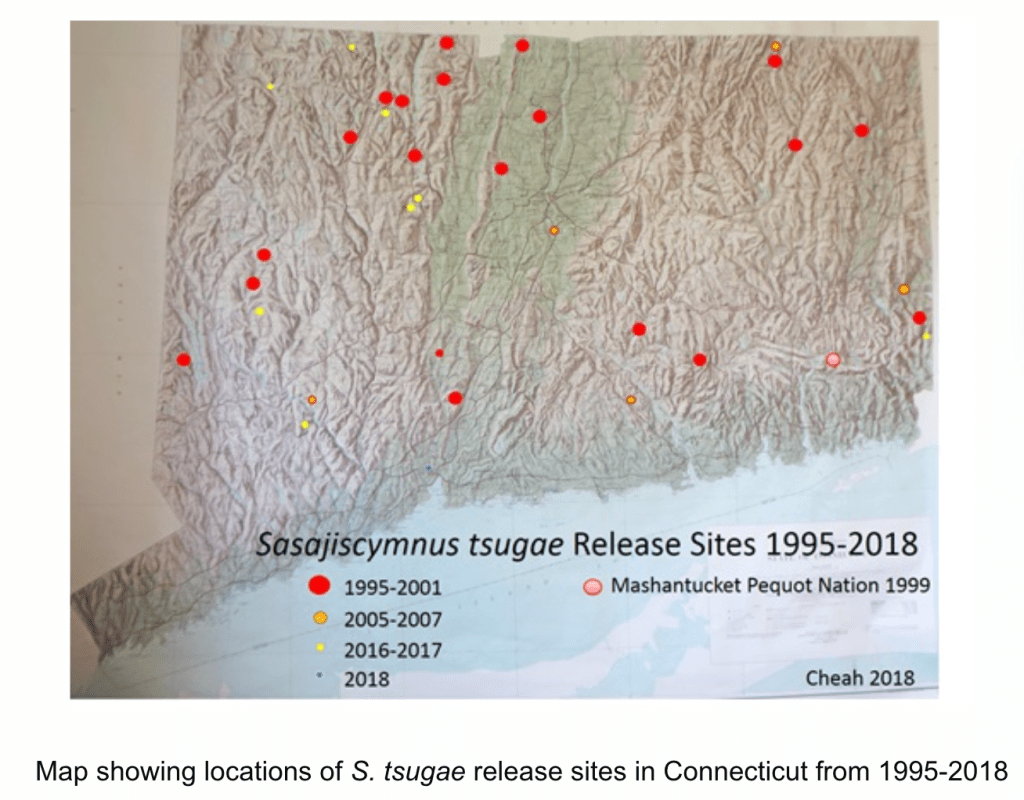

Cheah, a research entomologist with the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, has been releasing beetles from Japan in Connecticut for nearly 30 years, using HWA’s native predators to combat the pests’ devastation in CT hemlocks, Connecticut Public Radio reported in September.

Cheah and CAES reared over 176,000 of the beetles, Sasajiscymnus tsugae, in a research lab between 1995 to 2007, CT Public Radio said. But since federal funding dried up, Cheah has since personally managed the project, partnering with various foresters and natural resource conservation managers to purchase and deploy the beetles.

In addition, while warmer winters attributable to climate change have further threatened much of the tree’s native range, Connecticut has seen a silver lining as it relates to this particular species.

As a result of a rapidly warming Arctic, weaker polar vortex events have resulted in winter releases of “bitter Arctic cold into the lower latitudes,” which has resulting in more severe, short-lived cold spells that are able to sufficient to freeze out over 95% to 99% of the pest statewide. Biological control, like the ladybeetle released by Cheah, “can be implemented to target any HWA resurgence in the forest,” she says in the 2019 research paper.

“Based on what I’ve been seeing, the recovery in the forest, recovery of the trees, and the drop in the Adelgid populations, it’s been very encouraging,” Cheah told Connecticut Public Radio.

“So the turn tables have turned and hemlock are now experiencing an extended reprieve from HWA, although EHS remains a challenge and continues to impact hemlock health on stressed sites as the latter are not as susceptible to winter extremes,” Cheah says.

In recent years, while HWA infestations have greatly declined due to winter kill, EHS has spread to very damaging levels in western Connecticut, with elongate hemlock scale populations steadily rising and spreading east of the Connecticut River, Cheah says in a 2018 CAES fact sheet.

“To develop HWA resistance, first we need to find HWA tolerant and resistant trees in the wild. To do this, we need partners to help us find hemlocks that have survived HWA (even if they aren’t in pristine condition post-infection),” Haynes wrote in the Autumn 2024 issue of From the Ground Up, a quarterly periodical that aims to bring together “organizations and individuals working together toward a collective vision for the future of New England.”

Leave a comment